Reading Wright, JVG, Chapter 5

The Praxis of a Prophet

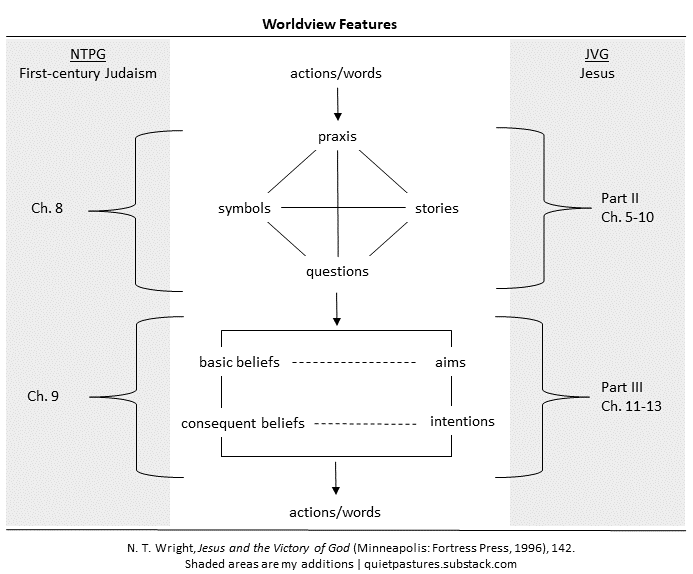

Chapter 5 of Jesus and the Victory of God (pp. 147-97) begins Part II of the book, as Wright explores the intersection of the first-century Jewish worldview and the similarities and dissimilarities of Jesus. This second part covers the diamond part of the chart below, with this chapter discussing praxis:

Because of the negative connotation of the word praxis with critical theory and Marxism, understand that this word praxis simply means a habitual practice or custom. I typically read it as a synonym for ‘action,’ but it is customary action, repeated action coming from one’s worldview. One’s praxis becomes an indicator—a signal—for a worldview. For example, sabbath is a symbol. Practicing the sabbath regularly in specific ways is praxis. That may indicate something about your worldview. Wright is examining Jesus’ habitual actions and ways he expresses himself as a way to get to his worldview and then to contrast it to the typical first-century Jewish worldview.

What are some of Jesus’ customary actions? “Jesus habitually went about from village to village, speaking of the kingdom of the god of Israel, and celebrating this kingdom in various ways, not least in sharing meals with all and sundry.” (p. 150) He’s an itinerant preacher and shares table fellowship with everyone—sinners included! An itinerant preacher is not unusual for first-century, but to share table fellowship indiscriminately is rather shocking.

Wright proposes the best model to understand this praxis is “that of a prophet bearing an urgent, eschatological, and indeed apocalyptic, message for Israel.” (p. 150) To this, we might say ‘duh,’ but remember that Wright is responding to the second (new) quest that attempted to make Jesus a cynic or a ‘teacher of timeless truths.’ Quite the contrary, firmly in the Jewish tradition, the initial model for Jesus is that of a prophet—an ‘oracular’ prophet (pp. 162-68) and a ‘leadership’ prophet (pp. 168-70). The former, like Elijah, Elisha, Jeremiah, etc., with oracles of judgment and call to repentance; the latter, synonymous with Luke’s description of one ‘mighty in word and deed.’ (p. 168, Luke 24:19; think Moses). Jesus is intentionally acting in ways that mimic the model the people of Israel have of the ‘prophets of old,’ as he speaks and acts in ways like them. “We find Jesus deliberately adopting a praxis which can function in our investigation as a way in to his mindset, his own variant on the worldview of those around him. He was combining in a new way the prophetic styles of oracular prophets on the one hand and leaders of renewal movements on the other.” (p. 169)

What then does the praxis of this prophet suggest? For this, I must quote Wright at length—this is the key to the argument of his book:

“Jesus was affirming the basic beliefs and aspirations of the kingdom: Israel’s god is lord of the world, and, if Israel is still languishing in misery, he must act to defeat her enemies and vindicate her. Jesus was not doing away with that basic Jewish paradigm. He was reaffirming it most strongly—and, as I shall argue later, in what he saw as the only possible way. He was, however, redefining the Israel that was to be vindicated, and hence was also redrawing Israel’s picture of her true enemies… Jesus, then, was offering the long-awaited renewal and restoration, but on new terms and with new goals. He was telling the story of Israel, giving it a drastic new twist, and inviting his hearers to make it their own, to heed his warnings and follow his invitation.” (p. 173, emphasis mine)

In other words, Jesus is arguing from within the Jewish worldview for a paradigm shift in the means and manner for achieving their long-awaited hope. Jesus announces this through parables (pp. 174-82), judgment (pp. 182-86), and miracles (pp. 186-96).

I’ll wrap this post up with focusing very briefly on Wright’s observation on miracles. He notes that these “could be seen as the restoration to membership in Israel of those who, through sickness or whatever, had been excluded as ritually unclean. The healings thus function in exact parallel with the welcome of sinners.” (p. 191) In other words, Jesus is inviting outcasts into the kingdom of God and restoring them as he does so.

But Jesus is more than a prophet. As we move to the next chapters, Wright will take us further as we examine the stories and understand that Jesus “really did believe he was inaugurating the kingdom.” (p. 197)

Chapter 1: Jesus Then and Now

Chapter 2: Heavy Traffic on Wredebahn: The ‘New Quest’ Renewed

Chapter 3: Back to the Future: The ‘Third Quest’

Chapter 4: Prodigals and Paradigms

Chapter 5: The Praxis of a Prophet

Chapter 6: Stories of the Kingdom (1): Announcement

Chapter 7: Stories of the Kingdom (2)

Chapter 8: Stories of the Kingdom (3): Judgment and Vindication

Chapter 9: Symbol and Controversy

Chapter 10: The Questions of the Kingdom

Chapter 11: Jesus and Israel: The Meaning of Messiahship

Chapter 12: The Reasons for Jesus’ Crucifixion

Chapter 13: The Return of the King

Chapter 14: Results