Reading Wright, JVG, Chapter 9

Symbol and Controversy

We continue in chapter 9 of Jesus and the Victory of God (pp. 369-442) on symbol and controversy. How did Jesus take the existing symbols of first-century Israel and redefine or reinterpret them and would this have caused major controversy? To the latter question, yes, to the point of death!

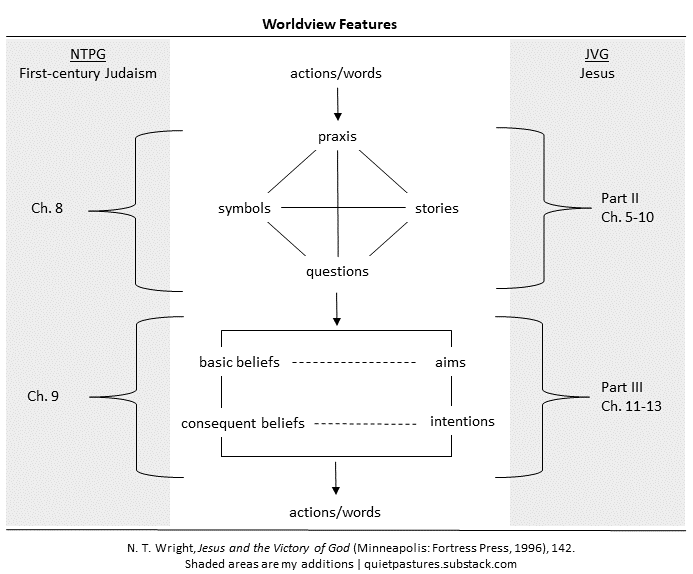

As a reminder of where we are and where we are going, refer to the following:

We have been through the praxis of a prophet (chapter 5) and the stories of the kingdom (chapters 6, 7a b c d, 8). We now tackle symbols (chapter 9). In chapter 10, we will finish the diamond with answers to the questions.

Wright notes at the opening of chapter 9 that when one plays with “cherished symbols,” one plays with fire (p. 369). Think of temple, Sabbath, or foods. What generates more anger from the Pharisees: telling a controversial story, or healing on the Sabbath and predicting the temple’s destruction? In the gospel of Mark, the ‘inciting moment’ is precisely the issue of the Sabbath, ending in 3:6, “The Pharisees went out and immediately began conspiring with the Herodians against Him, as to how they might destroy Him.”

The controversies in the Gospels, Wright argues, “were about eschatology and politics, not religion and morality. Eschatology: Israel’s hope was being realized, but it was happening in Jesus’ way... Politics: the kingdom Jesus was announcing was undermining, rather than underwriting, the revolutionary anti-pagan zeal” of first-century Israel (p. 372). Jesus isn’t the kind of king they expected (or wanted). His kingdom isn’t the kind of kingdom they desire. His message isn’t one they want to hear. And worse, he clashes with them over the very symbols they cherish, in which they have placed their national identity. These symbols, such as the temple, now were “operating in a way that was destructive both to those involved, and more importantly, to the will of YHWH for his people Israel.” (p. 433) Recall from NTPG chapter 7:

“The Pharisaic agenda [was]… to purify Israel by summoning her to return to the true ancestral traditions; to restore Israel to her independent theocratic status; and to be, as a pressure group, in the vanguard of such movements by the study and practice of Torah.” (p 189) In other words, they were both zealous and studious (p 190). Many of the revolts Wright describes were driven by, or at least involved, Pharisees! They went further than most in their attempts to “maintain a purity at a degree higher than prescribed in the Hebrew Bible for ordinary Jews.” (p 195) Ultimately, they believed “Israel’s god will act; but loyal Jews may well be required as the agents and instruments of that divine action.” (p 201)

Jesus walks in and tells them they have it all wrong! Rather than being the agents of divine action, they are in opposition to it! Rather than being a blessing to the world, they are actively working against it. If you are a zealous Pharisee (but I repeat myself), this is the last thing you want—indeed, have the capacity—to hear. Your primary criterion for evaluating a “would-be kingdom-bringer” is: do you “affirm the key symbols of zealous Israel?” (p. 395) Even further, do you affirm it the way we do? (p. 396). Jesus does not.

The Sabbath, one of the ten commandments, is given by God. Numbers records a man gathering wood on the Sabbath and is put to death for doing so (Nu. 15:32-36). Wasn’t Moses zealous for the Torah? Yet Jesus’ disciples pick grain on the Sabbath, Jesus heals on it, and He claims to be Lord of it (Mk. 2:23-3:6)! Blasphemy! The Sabbath healings are a great example of an enacted parable. Israel is in bondage, in exile, and in Jesus the Messiah, those healed are being released. “[Jesus’] claim was that the sabbath day was the most appropriate day [for healing], because that day celebrated release from captivity, from bondage, as well as from work.” (p. 394, emphasis original) For a Pharisee, the way to bring about the end of exile is to double down on Torah observance. Draw an even higher fence around Sabbath. Jesus stomps all over that and claims the authority to define Sabbath boundaries—further, He’s claiming that his actions are Sabbath. His disciples can pick grain because like David, Jesus is King, but unlike David, He is also Lord of the Sabbath (Mk. 2:28). He created Sabbath. When the bridegroom has come, the celebration begins!

You could say that the temple was the first century Jewish equivalent of our ‘the third rail of politics.’ Touch it and die. Jesus predicts its destruction, then disrupts its activities when he casts out the money changers (Mk. 11:15-18). Wright notes that the Greek term lestes (‘thieves’) used in the first century is bandits, or, revolutionaries. “The temple had become, in Jesus’ day as in Jeremiah’s, the talisman of nationalist violence, the guarantee that YHWH would act for Israel and defend her against her enemies.” (p. 420). Notice Mark sandwiches the cursing of the fig tree and its withering around the temple money-changers’ scene (Mk. 11:12-14, 15-18, 19-25). Like the fig tree, Jesus walks into the temple (and Israel!) expecting to see fruit and instead sees ‘violence’ (recall the parable of the vine growers and the owner [Lk. 20:9-18]). The tree is cursed. Both in his temple action and with the fig tree, we see again an enacted parable. Israel has no fruit. Temple sacrifices will be stopped—permanently—when it is destroyed. The fig tree dies.

Saying these things about the temple, or about Sabbath, is not a good way to ‘win friends and influence people’ in first century Jewish culture. It is the fast track to getting killed. If Mark and Luke’s chronology are followed, this is exactly what happens within a week.

One of the surprising conclusions that emerged from reading these chapters is that I discovered that the Pharisees, far from being a blind group (how could they miss Jesus?), were very reasonable! In fact, had I been a Jew of the first century, I would probably be one of them. Jesus is saying very radical things! It is only that two thousand years have passed and those sayings now seem normal to us. But in the first-century, Jesus is the radical! He’s not teaching morals, he’s teaching heresy—or, tiniest chance, not worth considering, he’s telling the truth! If you’re a Pharisee, you’re not going with the latter odds. Many radicals end up crucified. None of them came back from the dead.

But Jesus does. And that changes everything.

Chapter 1: Jesus Then and Now

Chapter 2: Heavy Traffic on Wredebahn: The ‘New Quest’ Renewed

Chapter 3: Back to the Future: The ‘Third Quest’

Chapter 4: Prodigals and Paradigms

Chapter 5: The Praxis of a Prophet

Chapter 6: Stories of the Kingdom (1): Announcement

Chapter 7: Stories of the Kingdom (2)

Chapter 8: Stories of the Kingdom (3): Judgment and Vindication

Chapter 9: Symbol and Controversy

Chapter 10: The Questions of the Kingdom

Chapter 11: Jesus and Israel: The Meaning of Messiahship

Chapter 12: The Reasons for Jesus’ Crucifixion

Chapter 13: The Return of the King

Chapter 14: Results